“Thru These Portals Pass the Most Beautiful Girls in the World.” Earl Carroll Theater, Hollywood. Credit: Shirley Claire @ earlcarrollgirls.com

The waves of beautiful faces, of bright mouths and of perfect limbs washed over the riveting gazes of admirers at the Earl Carroll Theatre in Hollywood, the flashy theater-restaurant that, in the 1940’s, prefigured the glamour of Vegas.

Undamaged and innocent, the beautiful women on stage evoked an overwhelming desire that their moment would come, soon, before they would have to scatter and discover random fates when the spotlight was no longer.

A beauty among beauties at Earl Carroll, Beverly was uncommonly radiant: silken legs, golden blonde locks, and blue oceanic eyes. Elegant, eloquent and breathing self-esteem, her destiny had a focus, a place: Paris.

In the 1950’s, Paris, reawakened and abounding with Americans of talent and ambition, was a city that she had been bred for. There, she came into the orbit of the celebrated illustrator and storyteller Ludwig Bemelmans.

Her beauty, her irresistible charm, and her love affair with Armand, a French count, inspired Bemelmans’ dazzling imagination when he was living on the banks of Seine.

Bemelmans published, in October, 1957, a novel, The Woman of My Life. Beverly is the woman. Her identity – revealed to me at by surprise – I am now obliged to share.

There is another story, a tranche of her life, that I place, carefully, alongside his. Like some ravishing women, she would trust her life to men, alas, foreboding trouble.

Beverly becomes a conduit for the stories of others who touched her life in Paris in the 1950’s: Le beau monde, art, and the implacable power of love.

Voilà, the stage is empty. The curtain rises. The actors take their places.

Ludwig Bemelmans

We all have access to the donnée of the life of Ludwig Bemelmans, the gifted illustrator and author of more than forty books. Millions know him through the creation of Madeline, a French gamine, and her adventures in a series of children books.

New Yorkers, with a hint of society, relish his delightful murals of Central Park that grace Bemelmans Bar at the Carlyle Hotel.

Bemelmans was un homme déraciné. A tumultuous childhood: born in the Austrian Tyrol, raised by a French governess who became pregnant by his father and commited suicide, abandoned by his father, shuffled off with his pregnant mother to her family in Germany, kicked back to his uncle, and then sent off to New York in 1914, at the age of 16, for a brief failed reunion with his father. Stupefying.

His youth endued him with the will and energy that Hemingway had written about to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “You just have to go on when it is worst and most helpless.” Going on was Bemelmans’ distinction.

Hotels would harbour him. He spent 15 years at the Ritz Carlton. In 1947, the murals at the Carlyle paid for 18 months of his family’s room and board. He would own no property in New York.

He was an autodidact. Bemelmans dedicated himself to the craft of writing and drawing. He incarnated Nora Ephron’s credo that “everything was copy.” Moreover, everything was scenes to illustrate.

The forces that shaped Bemelmans, and the trajectory of his artistry, are chronicled in Bemelmans: The Life and Art of Madeline’s Creator, written by his grandson John Bemelmans Marciano. A pleasurable read, the countless illustrations affirm a joyous talent.

As Forbes reported, the curators of Bemelmans’ brand – John Bemelmans Marciano and his mother Barbara Bemelmans – have leveraged Bemelmans’ creative gifts into a family business now worth millions.

If there is a great deal of the personality of Bemelmans, as revealed in his writings and in his sublime illustrations, there is very little in the book that is personal.

I want to contextualize the arc of Bemelmans’ days in France. In the case of Paris, the danger of it was financial and emotional dissolution.

Paris: La rue Gît-le-Cœur

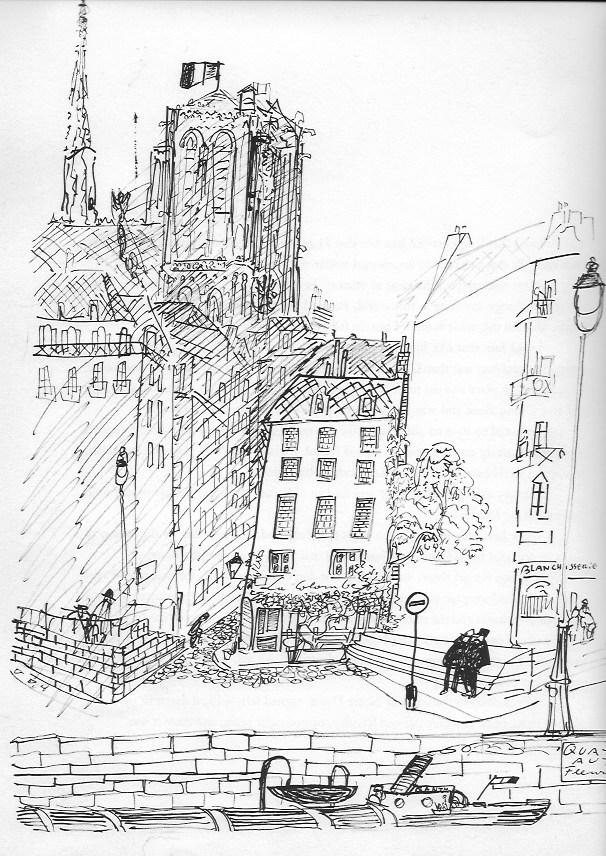

Yearning for his own nest in Paris, Bemelmans, in the early 1950’s, found a penthouse on the Left Bank of the Seine on the Quai des Grands-Augustins at Rue 1 Git-le-Coeur.

In his illustrated memoir My Life in Art, Bemelmans wrote: “It was the color of cold salmon….It had a two-person elevator, a statue of Rodin in the entrance hall. and the top floors were furnished like a country home in Westchester.” He sketched the “sweeping panorama of the city” from the penthouse’s terrace.

The penthouse belonged to a friend, Alice Antoinette DeLamar (1895-1983), who inherited, at the age of 23, a massive fortune. Was ascribing the decor to a Westchester home a gesture of privacy? Actually, Alice DeLamar had a residence in Weston CT.

The luxury of the setting, and the glorious views, are revealed in photographs in The Manuscript Hunter, a website dedicated to documenting the life of Alice DeLamar.

The rue Git-le-Coeur is part of Beat Generation lore, as at No. 9 is the Beat Hotel that took in Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Brion Gysin, among others.

On the Quai, a few paces down from 1 Git-le-Coeur, is La petite Ecluse des Grands-Augustins, a Bordelais wine bar that was, during my days on rue Dauphine, the mise en scène for intimate hours etched fiercely in memory.

La Colombe: A Bistro and a Home

La Colombe, on the L’Ile de la Cité, Paris, drawn by Ludwig Bemelmans. Source: My Life in Art, 1958.

There is a feeling Bemelmans had — I have had it myself— that living in Paris is inspiring, though it is not sufficient. You desire to possess something to achieve a sense of belonging there.

In 1953, something in Bemelmans responded to this need. He purchased a building on the north edge of L’Ile de la Cite on rue Colombe, the entrance facing onto the Quai des Fleurs.

“It was precisely what I had been looking for—a lovely house, half palace, half ruin, an old house covered partly with vine,” Bemelmans wrote in My Life in Art. “It had a bistro on the ground floor frequented by clochards and a small garden in front in which people sat.”

His dream, vivid to the point of ecstasy, was to revel in an artistic, social and culinary existence amidst the glamour of Paris, all under one roof.

It was a building dilapidated by neglect, a financial sinkhole. Costs skyrocketed due to delays in acquiring construction permits, and to extensive renovations.

The most frustrating obstacle was the lack of sewer lines. There were no bathrooms. Bemelmans rigged up a taxi with doors designated “Mesdames” and “Messieurs” for transporting guests to relief nearby.

Bemelmans’ dream of entertaining Le Tout Paris, and its posh English-speaking counterpart, was destined to vanish. La Colombe closed after a few months. The building passed into the hands of Michel Valette (1928 – 2016) and his wife Beleine.

The Paris Murals: Rescued

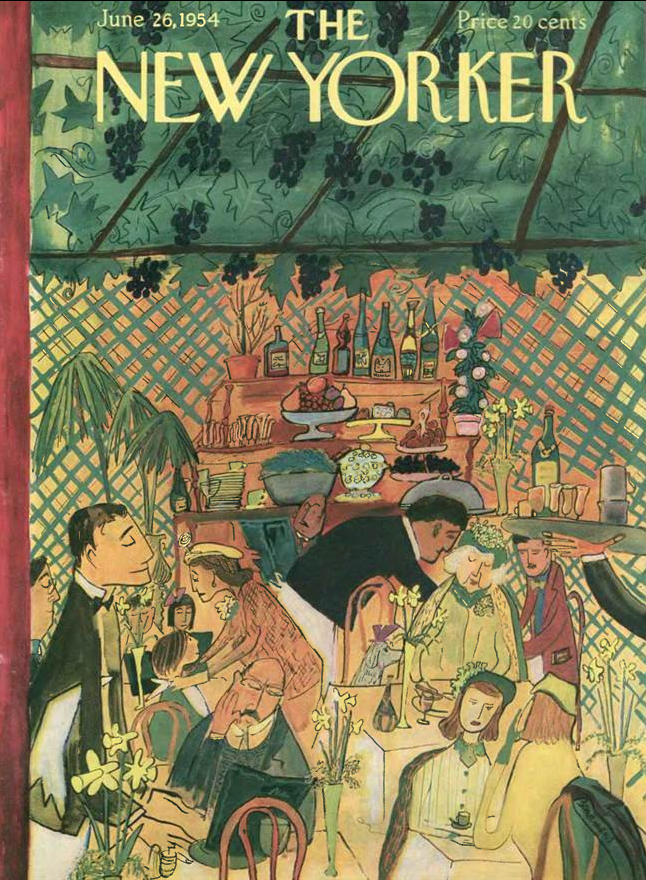

Bemelmans decorated the walls of La Colombe with lively images of la bonne table. In contrast to fanciful images of animals posing as humans in Central Park on the walls at Bemelmans Bar in New York, the walls of La Colombe evoked the gaiety of les dîners en ville.

A variation on the Paris frescoes appeared on the cover of The New Yorker – the magazine featured many covers by Bemelmans over the years – in June, 1954.

New Yorker Cover of June 24, 1954, Artwork by Ludwig Bemelmans

In October, 1954, Michel Valette and his wife Beleine opened La Colombe as a cabaret bistro. In 1962, there was a change in labor laws whereby artists were classified as employees. The social charges and taxes were onerous, forcing La Colombe, in 1964, to close down as a cabaret.

From 1964 to 1985, La Colombe was a 3-star restaurant with Beleine Valette as chef. When the space was sold in 1985, Michel and Beleine preserved the frescoes of Bemelmans, placing them in storage. Michel Valette describes this rescue operation in his book, yet to be published.

The frescos would have passed from sight if not for the vigilance of Jane Bayard Curley, the curator of a 2014 exhibition at New York Historical Society: “Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans.”

The year: 2012. How Jane must have trembled with pure excitement, like finding a precious jewel in an old drawer, when, at a public auction, she discovered five frescoes of Bemelmans from La Colombe.

Jane’s heightened sensitivity to Bemelmans’ artistry was shared by the fervid art collectors Charles and Deborah Royce. The frescoes underwent a six-month restoration at the Center Art Studio in New York where conservators restored the original vibrant brushwork.

It was to the Ocean House Hotel in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, that Charles and Deborah Royce joined the La Colombe murals with 21 illustrations of Bemelmans, as well as two panels, from a total of fifteen, that were originally commissioned by Aristotle Onassis in 1953 for the playroom of Onassis’s yacht Christina O.

At the Ocean House Hotel, you have the satisfaction of knowing that, despite any misfortunes, these delightful artistic creations were fated to reside in a common space.

Ludwig Bemelmans Enraptured

In My Life in Art, Bemelmans’ elaboration on how he found La Colombe is incompatible with a someone of his station in high society. After several interchanges with Bemelmans, a clochard (a vagrant) leads him to the decrepit property.

Michel Valette provided me with some nuance. Bemelman’s decision to sell La Colombe, at what Valette referred to as a bargain basement price, was precipitated by a désespoir d’amour – the lose of a love object that shattered all hope and all joy.

In retrospect, it was this younger woman who had led Bemelmans to La Colombe. The entire project was a grand romantic adventure. It was out of that excitement, finding love where he thought there had been none, that Bemelmans envisioned a rhapsodic passage to a new life.

He must have had the sensation that Hemingway felt it in the Sun Also Rises: “of things coming that you could not prevent happening.” That Bemelmans would never arouse her love in return was a discovery that made the sale of La Colombe unavoidably poignant.

Her name was Régine, according to Jane Bayard Curley. Worse still, Jane messaged me, was the suitor that Régine eloped with: Henry Freund, the younger brother of Bemelmans’ wife. Shattering.

In escaping emotional and financial ruin, Bemelmans was emboldened by the company of Count Amand. By 1957, when they passed time together at the artist’s studio outside of Paris, Bemelmans was preparing for a one-man show of his oil paintings at the Galerie Durand-Ruel that fall. A new dawn, as a painter.

Armand II de La Rochefoucauld

Among the French nobility, La Rochefoucauld is among the most illustrious families, their origins dating to the 10th and 11th centuries.

The Count Armand de La Rochefoucauld (1902-1995) befriended Ludwig Bemelmans in Paris in the late 1940’s. In The World of Bemelmans, published in 1955, Armand is identified as a habituée of the chic bistro Le Montana on the left bank, and an investor in a seedy bistro, Le Petit Balcon.

Although single at the time, Armand had a son, Armand III, born in Lisbon in 1944, out of wedlock to Renée Brandt, whom he never married and whom never took a noble title.

Armand was, as his son attested, un fétard, a man who was fond of drink, bars and clubs, and women, preferably vivacious.

Michel Valette informed me that Armand was a bit louche, having made several appearances at La Colombe, in 1954, after Michel had reopened it as a cabaret.

Armand had been engaged to Beverly, an American identified as Evelyn in The Woman of My Life. A strong current of emotion passed through them, a profound attraction. She marked him with an indissoluble appreciation for high tone women whose langue maternelle was English.

A cocktail of beauty, ambition and wealth, Esther Millicent Clarke intoxicated Armand at first sight. Born to a British father and Japanese mother in Tokyo, interned by the Japanese in the Philippines at the outbreak of World War II after which time she emigrated to the United States. Divorced, Esther had been married to a rich Californian.

The youthful Esther, 35, came to Paris in 1956. Her daughter, Cheryl Nesbitt, attended a posh private school in Switzerland. At last, a beautiful woman who had seen more of the world than Armand, 54, had.

Shunning disfavor by Armand’s kin, they snuck off to Saanen, Switzerland where they wed on Feb. 5, 1957. A daughter Lise was born in 1958.

The year is 1957. In photographs with his close friend Ludwig Bemelmans at Ville D’Avray, Armand, now married, appears relaxed in a sport coat and tie. A catered lunch. A stroll along a pond.

Their turmoils were behind them. They appear at ease with life and drawn close to its essence.

Armand had finally turned to a life in the tranquil broad wake of French nobility that he had envisioned. The seas had calmed. His course was fixed.

Chateau de La Rochefoucauld, La Charente, where Armand III married in 2007

Armand III – L’Enfant Terrible of French Nobility

Turbulence of la première classe: Count Armand III de La Rochefoucauld lived on the lam, as a wanted man, in the 1990’s.

A swindler extraordinaire, listed by Interpol in about 90 countries, he was convicted four times in several countries for passing fake travelers cheques and false identities.

In the states, Armand III’s notoriety would have spawned his own version of “Celebrity Aristocrat,” have had him on late night chat shows, and giving motivational speeches at addiction clinics.

The French harbour no such sentiments for royals. In 2015, police raided his property and discovered passports with a photo of Armand III in numerous false identities, 3,000 euros in his pocket, and more than 1 million in fake travelers cheques.

Despite his protest that all this was vestiges of a former life, he was jailed. I imagine he was mouthing words of F. Scott Fitzgerald: “It’s happened to me before but never like this – so accidental – just when everything was going well.”

After 14 months, he was freed without charges being filed. Upon his return, he learned that the court was confiscating his cherished classic cars: a 1952 Cadillac Eldorado, and a 1955 Buick that had been owned by Cary Grant.

It was a deep dormant wound, waiting to be evoked by opportunity, that led to his impossible behavior.

The resentment, he opined, of being declared a “bastard” at the age of twelve when his father, who never wed Armand III’s mother, Renée Brandt, married Esther Millicent Clarke.

He was barely 12. His family refused to acknowledge him in public. His grandfather deemed in his will for Armand III to remain childless so that his illegitimate birth would result in no heirs. His uncle became his paternal figure.

A conjugal life arrived in 2007 when he married Anne Caroline Landal des Essars, 25 years his junior. They decamped to a manor house in Normandy.

Armand III settled a score with his grandfather. He became a progéniteur: three daughters, the youngest was only ten days old when he was hauled off to la tôle (jail).

In interviews, he has a condescending casualness towards his persecutors, as if his transgressions were mere adolescent pranks.

Armand III’s fashion style is “monogrammed slippers”: dated opulence, with a dash of decadence. Fragrance? My hunch: Guerlain’s Habit Rouge.

He is sustained indomitably by his wife Anne Caroline. I place his story here with the belief that he may have viewed, during his childhood, the gracious silhouette of Beverly. On March 23, I received an email from Armand III, who wrote:

I very well remember Beverly. Beautiful woman, living rue de l’Université, ground floor, on the right. I even remember the furniture, very 1930/1940. I often pass by, asking myself what became of her. My father wasn’t “engaged” to her, but very much in love.

The Woman of My Life

Published in October, 1957, The Woman of My Life recounts the adventures of Armand, a French Duke, in his search for the love of his life.

The opening passage is a reverie to Evelyn, which fills an entire page in John Bemelmans Marciano’s book. However, this tribute could represent Bemelmans’ channeling his devotion for Régine.

Along the way, the Duke has to overcome a fear of women, and perhaps an inborn indifference to females. Towards the end of the book, he loses a woman, who was “the woman of his life,” to a younger suitor, a situation that mirrors his rejection by Régine.

Evelyn, the American beauty, is the ever-present force who perseveres in her devotion. The narrative closes with Armand and Evelyn boarding a boat at Le Havre for America, a marriage to follow on board.

John Bemelmans Marciano asserts that the book is “loosely based on the life of Armand de la Rouchefoucauld (sic). This strikes me as dubious. It’s more of an imaginative tribute to Armand, and to Beverly, inspired by common experiences.

The New York Times accorded The Woman of My Life cheerful praise.

Beverly

Among the ephemera that my mother left in boxes, I discovered the book The Woman of My Life. Instantly, I recognized the author from evenings of merriment at Bemelmans Bar in my days, those endless days, in New York.

I opened the book. Letters and cards fell to my feet. I felt a tinge of excitement. Fragments of an inner life revealed to me. Et voila, Beverly writes:

“The Woman of My Life is about my Paris adventures (I am Evelyn) and Armand is my ex-fiancé.”

Beverly was a dear friend of my mother at the time when they both performed at the Earl Carroll Theater.

Radiant with ambition, savage with youth, and armed with beauty, they came to Hollywood full of brave illusions. They ran together, and ran away from men who were no good. The mobster Mickey Cohen, for one.

Beverly was seductive, and at the same time untrusting, as life had already taught her some hard lessons. She had two young daughters to support, and, as a consequence, she devoted herself to men of a certain standing.

How she arrived in Paris in the early 1950’s is a mystery. She must have known that the move marked a turning point in her life, out of line with everything that had preceded it. According to Armand III, Beverly knew Esther Millicent Clarke prior to Esther’s marriage to Armand II.

In Paris, she reveled in hosting cocktails and dinners for American expats. She kept up with the gossip on celebrities in from New York and the coast.

Beverly wasn’t into boozing coupled with venery of the Paris Review crowd, rituals that co-founder George Plimpton imported back to his native city. She did not hang out in cafés. Hers was a more serious world where her daughters, and love, were all consuming.

Armand is a “gentleman.” She knows that there is real passion there, yet she realizes that whatever splendor she evokes in his heart is inadequate for him to become a father for her girls.

In 1957, there was trouble:

“Well, I have had no luck. I married an Arabian prince in the Mosquée, but before we could have a civil marriage, he was sent off to prison for I don’t know how long. (Being one of the leaders of the rebellion.) And I’m told the marriage isn’t legal – I don’t know what to do.”

The truth is in the stars. They had lost their shimmer. I am confidant that Beverly regained their light again, incandescent as ever.

The Girls

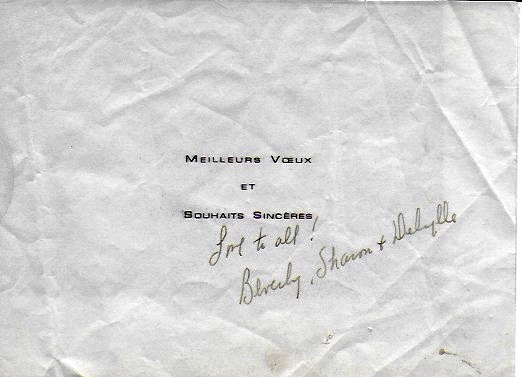

It is Christmas, 1957. Her girls at the doorway to adulthood, eager to launch themselves into the world, and she, dangling, suspended in time. In Beverly’s own tender hand:

“Delylle is 15 now and very pretty. She thinks she is Brigit Bardot for the moment. She is very French in her ways – but an Elvis Presley fan and did you know that the James Dean cult and Elvis Presley mania has crept into the continent.

“Sharon is very lovely and serious. She has decided to study medicine and will enroll later La faculté de Médecine. She is now 17.”

Holiday Greetings from Beverly in Paris, Christmas, 1957

Note: Since publication of this article, Beverly revealed as Beverly McKie (née O’Brien), AKA O’Brien-Samana. Her daughters: Sharon Diane McKie and Delylle Ann McKie.

Paris: Le Dôme

An early evening in January last year, when an eerie calm draped over terror-weary Paris, I dined with an esteemed American attorney, of the art world, in the front room of Le Dôme in Montparnasse.

Sitting on a banquette, while the attentive waiter explained the wine list, a young woman walked in, and slipping out of an elegant black coat, looked back toward us, exposing an open face, warm, unhurried, her watery blonde hair brushing her soft features. I saw her smile.

I flinched, and recognized her instantly: Beverly, at twenty-six, at the Earl Carroll Theater, fresh, vital, and totally unaware of what one day she would come to experience in Paris.

I was plunged into panic trying to imagine what Beverly did become, and how her girls, Sharon and Delyelle, got on with their lives in Paris, or elsewhere.

I thought of the city that lay all around me in dawn and darkness, the lights dancing off of the Seine. Down through the years, among the thousands of passive faces in the Metro, the expressions of wonder at vernissages and of joy at restaurants, did I gaze, uninformed, for a fleeting moment, at Beverly, Sharon or Delyelle?

A sentimental notion. I yield to the remorseless truth: I came too late to the party. Paris holds secrets that it never unveils.