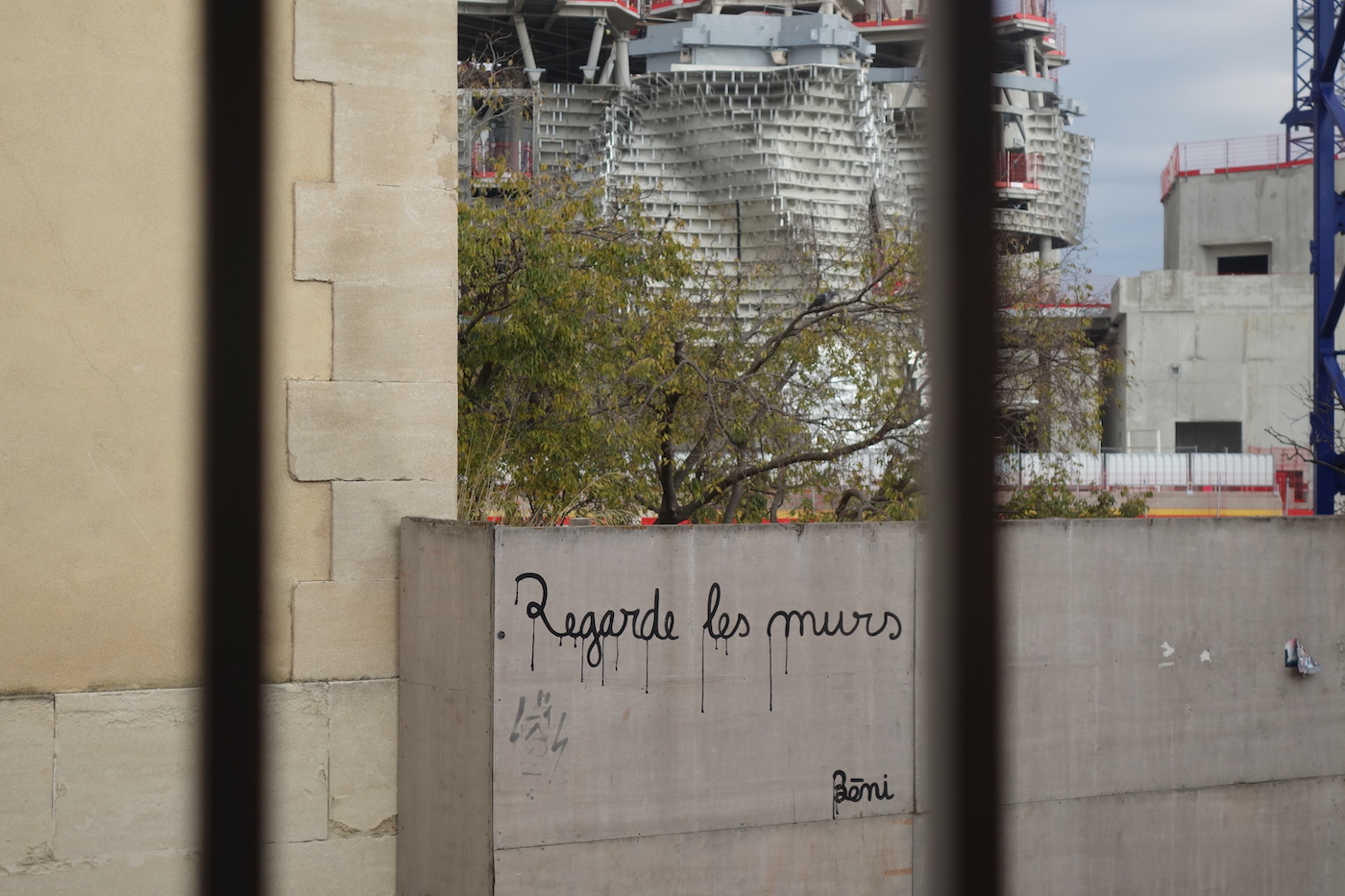

Frank Gehry-designed tower at Luma Arles.

Breaking:

June 2024: Tickets to reserve time slots to visit Gehry’s tower from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 pm (last entry). Ticket includes entry to all exhibitions and public garden:

Spring, 2020: Luma Arles and Les Rencontres d’Arles entered into a partnership on exhibition space for the photography festival at Luma Arles beginning in 2020, announced former mayor Hervé Schiavetti at Paris press event announcing the 2020 festival program. Agreement is for five years. Alas, agreement delayed until 2021.

Gehry in Arles

At first approach from the Avenue Victor Hugo in central Arles, there is something about Frank Gehry’s stainless steel-cladded tower glistening amid the faded camel, umber, rose colors of a timeworn landscape. It sits defiant, like a remonstrance.

Perched on a plinth and rising from 54-foot glass atrium, the soaring 170-foot tower is a 53,000 square-feet surface of metal panels supporting more than 10,000 blocks of gleaming hammered stainless steel.

The nexus of a complex, known as Luma Arles, the structure will be home to the Luma Foundation, created by Maja Hoffmann, a pharmaceutical heiress (Hoffmann-La Roche) and high-spirited (fougueuse) patron of the arts.

The Luma Foundation supports independent artists, and facilitates discourse and inventiveness by sponsoring cultural, educational and the environmental initiatives.

You can take Frank Gehry’s tower as a twisting tornado, as one architecture critic put it, or you can dismiss it as a beer can (une canette) like certain locals do who don’t get anything.

Or you come to understand it as I do, as the legacy of an indissoluble engagement to art and to the environment — the empowerment to create and preserve unalterable beauty.

Engagement: The Environment

A Swiss doctoral student, Luc Hoffmann (1923-2016) came after the war to the Camargue, the wild humid delta of brine lagoons and marshes, that stretches from the south of Arles to the Mediterranean sea. At first sight, he was in its thrall. For his thesis, he studied the chicks of the common tern. So, it began. A lifelong engagement. His dedication to the Camargue was pure, even angelic. Luc Hoffmann was like a revolutionary: one gave, everything, for the cause. His visionary existence required a base: he acquired the Tour de Valat estate in the heart of the Camargue. In 1954, he set up there a biological research institute that incarnates today the founder’s incorrigible determination. His passion for nature never faltered. Luc Hoffmann co-founded the World Wildlife Fund, and set up the Mava Foundation to fund conservation projects. 2012 saw the advent of the Luc Hoffmann Institute devoted to sustainable development.

Engagement: Art and Culture

In 1956, Luc Hoffman relocated the family to the Camargue. Over the course of the years, he exemplified to his children a life that had always been lived in accordance with a passion for engagement. For them, it must have been like learning some heroic language. Maja Hoffmann attended a school that her father established on the estate. She had a stint working at La Tour du Valat. Her father revealed an engagement to the world of nature to her, call it conservation; she came to add the universes of art, culture, education and human rights. In the end no one of them less precious than another. These values assert themselves in the Luma Foundation, which may be appreciated as a vital part of Maja Hoffmann’s own self-concept — deep convictions that are emotional and visceral, borne at a young age. Among the inhabitants of Arles, Maja Hoffmann is, simply, une fille du sud. (a girl of the south). For them, this trait is the predominant element in the donnée of her biography. As someone framed it to me in Arles, “Tout s’explique,” (explains everything). Her engagement is the ineluctable emotional force that drove her to do something of consequence that endures, as her father devoted his fortune to preserving the Camargue and the environment. It is an engagement that fueled her persistence, her intractability in pushing ahead against unforeseeable arduous circumstances — the impersonal and the personal. Among the ways of her family that Maja Hoffmann brought to Luma Arles are: discretion is good taste; words, well-chosen, are important, and the slightest ostentation is classless. So, our narrative begins. Voilà, the mis-en-scene.

Arles: Overwhelming Antiquity

On warm and muggy nights in Arles, the pace is languid. People sit at ease on the terrace, in awe of no one. There are no temptations as much as consolations of a leisurely evening.

In Arles, vestiges of an ancient past dismantles modern memory into sepia tones. The weary antediluvian panorama seems resistant to any fresh coat of modernism.

Perched on the Rhone in Southern France, Arles is a town where every public surface wears a patina of antiquity – cramped lurid biscuit-colored edifices and decaying gray stones.

Arles sided with Caesar over Pompey (Marseille), an alliance that brought prosperity in the 4th and 5th centuries. During 1888-89, van Gogh resided in Arles, memorializing the town in 300 paintings. Once a thriving port, Arles was relegated to a backwater with the arrival of the railroad.

Lacking any industrial base, Arles has struggled to prosper. Inhabitants refer to the town as broke (fauchée), its institutions starving (au pain sec).

Unemployment, which ran over 15% in recent years, now has dipped below 14%. Among the youth, the out-of-work tops 30%. A quarter of residents are retired. The haute bourgeoisie of Arles live elsewhere, in villages in the Alpilles like Saint Etienne du Grès and Mausanne.

“Arles is a town which is often forgotten..One time a year it reawakens for the photography festival.” Maja Hoffmann (Le Monde)

I know three Arles: One, the first ten days of July when the photo festival has splashy events; two, the other summer weeks when the festival brings in a steady stream of visitors, and the last, in the winter, a mirthless town of cold naked stones where inhabitants measure out the days in exact portions.

Journalists write about Luma Arles from afar, forgoing a visit. For one, Paul Goldberger, biographer of Frank Gehry (see below). And Art News, whose reporter last month misidentified Arles as “marshy wet lands” and as home to the Tour du Valat. No, it’s the Camargue.

Arles: Photography Magnificent

“To collect photographs is to collect the world.” Susan Sontag, On Photography

With art, inspiration is everything. One knows that instinctively. It hung over Lucien Clergue (1934-2014), and his friends in Arles like an unpronounced duty (un devoir). Lucien Clergue, a lifelong resident of Arles, was the first photographer to be elected to the Paris-based l’académie des Beaux-Arts, and to serve as its president.

In the late 1950’s, Clergue began to pester his childhood friend Jean-Maurice Rouquette, the curator of Arles’ Musée Réattu, about the absence of any museum in France with a dedicated collection of photography. In 1961, Clergue traveled to New York. His first stop was at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) to view Guernica by Picasso. As Clergue recounted in an oral history:

“At MOMA, to my great surprise, you had to go through rooms displaying black and white photographs to reach Guernica. I said to Jean-Maurice that to view the world’s greatest contemporary painting, you have to walk through photography. That moment in New York was capital in making us move forward.”

In 1965, the two men organized a mailing to photographers worldwide asking them to donate prints for the photography collection at the museum. Only two photographers refused to donate: Cartier-Bresson and Avedon. Other prints of Edward Weston were donated by Jerome Hill. With enough prints to display in a room, the Mayor of Arles was persuaded to give his consent for the the second floor of the Musée Réattu to be dedicated to photography. Before long came an opportunity for Arles to enlarge its footprint in photography. The annual Festival of Arles, caught up in the revolutionary fervor of 1968, was the target of calls to revamp its dull format. In an oral history, Roquette reminisced:

“We said that the only thing we have that is free is photography. We proposed bringing three photographers to present slides of their work in the reception room at City Hall. There were lines out the door until 3:00 a.m. The next year we set up about 400 chairs in the courtyard of the Musée Réattu. And it took off like that.”

With a photography festival in gear, Clergue began to network with photographers. In 1971, he made a world tour. In Carmel (CA), he met Ansel Adams. With its sparse resources, the nascent festival sponsored a trip for Ansel Adams. In 1974, Adams taught a workshop at the festival. When he returned home, Adams gave a press conference at which he applauded Arles for doing amazing things for photography . Adams’ participation at the festival was an imprimatur, a watershed moment that bequeathed Arles an unalterable destiny: a fervid summer festival for world photography – Les Rencontres d’Arles – that attracts today over 100,000 visitors. In the beginning: folding chairs.

Luma Arles: A Timeline

2004: Luma Foundation

Zurich-based Maja Hoffmann launches the Luma Foundation, named after her children Lucas and Marina.

2005: Frank Gehry

Maja Hoffmann meets Frank Gehry during the filming of Sketches of Frank Gehry, directed by Sidney Pollack, a documentary she co-produced.

2006: Economic Development Zone

On July 17, the City of Arles approves the creation of an economic development zone – ZAC des Ateliers – for the development of the Parc des Ateliers.

2007: AREA PACA

On June 12, the City Arles appoints AREA PACA, a regional manager of large public projects, to oversee and manage the development of the Parc des Ateliers.

2007-2008: A Bright and Shining Future for Arles

In 2007, Frank invited Maja to a dinner celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. She saw the “Bilbao effect” au premier rang. In Nov. 2007, Maja organized a trip to New York with the Mayor and others to meet with Frank Gehry. In December, 2007, the Luma Foundation announced a proposed project at the Parc des Ateliers, a 24-acres site that was once clusters of workshops (ateliers) for railroad maintenance and repair, near the center of Arles. On June 20, 2008, the Luma Foundation signed an agreement with AREA PACA concerning financial arrangements and costs. The Foundation was identified as an “acquisition candidate” for the Parc des Ateliers.

Luma Arles will be anchored by a 170-foot structure designed by Frank Gehry. This structure would serve as the headquarters of the Luma Foundation, and include exhibition space, a library, classrooms, archive storage, artists’ residences, and a cafe. Six existing structures will be renovated for exhibition space by Selldorf Architects in New York. The landscape architect, Bas Smets in Brussels, will design a 10-acre public park with hundreds of trees. The project at the Parc des Ateliers will be financed by the Luma Foundation with an original contribution of €100 million ($115M). Note: The investment today approaches €200 million. In July, 2008, Maja Hoffmann and Frank Gehry presented the project at Les Rencontres d’Arles, in the presence of the Minister of Culture Christine Albanel and Arles mayor Hervé Schiavetti. Frank Gehry proposed two-linked towers on varying heights located next to the renovated clusters of ateliers. The Luma Foundation’s campus will accommodate exhibitions during the annual summer photography festival.

2010: Venice Biennale

The Luma Foundation presented the maquette of its project at the Parc des Ateliers at the Venice Biennale. Photos of Maja Hoffmann and Frank Gehry, and of the presentation on ArchDaily.

2011: Le Choc. A Set Back

In an unnerving decision, in March the National Commission for Historical Sites and Monuments rejected two of the five building permits because the towers siting over an ancient Roman cemetery could threaten Arles’ Unesco World Heritage classification. In addition, the towers as obstructed views of a medieval church. The French Ministry of Culture concurred and recommended that the towers be repositioned on the site.

Steeling herself, Maja Hoffmann stated, “We are convinced that large-scale cultural projects involving private and public partnerships are possible in France and we want to find ways to make them workable.” The way to make Luma Arles workable was strenuous: redesign of the tower by Frank Gehry, and relocating it on the site.

2012: Le Parc des Ateliers

The Parc des Ateliers is drab and dreary vista. A grid of washed-out buildings and burned-out workshops stretch across a parched dirt surface sprinkled with scruffy haphazard plant life and weedy stubble. Many artists have complained about exhibiting in the worn-down ateliers which are at times flooded by summer storms or turned into furnaces on hot days. In 2012, the German photographer Andreas Gursky refused to exhibit at the festival in protest to the conditions.

2012: The Last Time

A beleaguered, yet determined, Maja Hoffman told a French photography website, that “twice,” and “without consultation,” public authorities have changed the criteria of the building permit and the area concerned. In a minatory bark she said, “It goes without saying that this time will be the last.”

In December 2012, the “last time” arrived when a revised design of Gehry’s tower and the Parc was formally presented by the project director Eric Perez, and Maja Hoffmann of the Luma Foundation.

The new design featured a single soaring 170-foot tower of twisted aluminum foam with a stone backbone, enveloped by a 54-foot glass rotunda and a landscaped courtyard, with 230 underground parking spaces. The tower has been displaced from its original proposed site, moved closer to the Avenue Victor Hugo.

Maja Hoffmann, hardened as she was (or is undoubtably is) by five years of delays and tedious negotiations, refused to release to the press the final designs until such time that the construction permits were issued.

2013: The Green Light

On July 10, Arles Mayor Hervé Schiavetti announced that the construction permits for the Luma Foundation had been approved and signed. There remained various administration procedures and the sale of land to complete before construction could proceed.

2013: François Hébel

Over the course of several years, I thought that I was watching some mordant tragedy playing out in Arles in which two driven individuals, both uncommonly self-possessed, were symbolically opposed. It was not merely that the world had set the two of them at odds. The end game meant that one of them must lose if the other were to win. In 1986, François Hébel took command of the Les Rencontres d’Arles. He launched the display of photographs in the dilapidated railroad workshops. The Parc des Ateliers evolved into a distinctive terrain at the festival. In 1987, Hébel brought to Arles the personal narrative of love and loss of Nan Golden: “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.” The iconic show brought a sunburst of aesthetic esteem to the festival. Despite two smashing years in Arles, Hébel left to direct Magnum Photos. François Hébel returned to Arles in 2001 as director of a festival heavily in debt with 95 percent of its funding from public sources. Attendance was averaging 9,000 per season. Maja Hoffmann supported the arrival of Hébel by creating, in 2002, the Prix Découverte, an annual prize recognizing young talent in photography. By 2013, Les Rencontres d’Arles had a robust balance sheet with 40 percent of funding coming from visitors, 40 percent from public funds, and 20 percent from sponsors. Attendance was exceeding 90,000.

2013: The Unraveling

The Parc des Ateliers, a thread woven into the tissue of the festival, became the cause of a long unraveling. Turning backwards to my visits to Arles before 2013, I recall hearing murmurs in the wings (les coulisses) that Hébel’s attitude towards the Luma Foundation had calcified into mistrust (méfiance). What haunted François Hébel was losing control over exhibition space in the renovated ateliers. Aggravated he was by Maja Hoffman’s intention to display at Luma Arles art from her private collection and from the family collection stored in Basel, and works acquired by the Foundation. There was another source for his pent-up frustrations. Hébel saw Arles as an orphan, ignored by carriéristes in the Culture Ministry who channel funds to glitzy festivals. In July, 2013, he put his sentiments, sarcastically, to Le Monde:

“The Cannes Film Festival has its Palace. We are boy scouts camping on the ground.”

François Hébel fought back. He pitched an International Center for Photography that would occupy the ateliers, permanently, sustained by a budget of 34 million euros. In effect, his audacious project would banish the Luma Foundation from the ateliers. I heard a gallery owner remark, “Quel culot!” (What nerve!) The denouement: construction permits were approved in July, and in the fall PACA, the regional government authority, agreed to sell the land of the ateliers to the Luma Foundation for 10 million euros. The coup humiliant (a humiliating blow) came on October 22 when the Culture Ministry rejected Hébel’s alternative proposal, preferring the private initiative of the Luma Foundation. Anti-climatic the moment was on Nov. 5 when Hébel shot off an impassioned five-page letter to Jean-Noël Jeanneney, president of the Festival, in which he announced his departure after the 2015 season, and elaborated on his frustrations and discontents.

Some exits are unforeseeable, even unimaginable. I submit that it was François Hébel’s hubris that put him in an untenable position. It blinded him to how unforgiving the machinery is behind progress. Alas, his letter to Jeanneney came off as petulant, his resignation as poignant, since his reign in Arles had an Athenian brilliance. A prince had fallen from the heights.

2014: The Groundbreaking

“Arles is such a beautiful city. I have tried not to blemish its beauty.” Frank Gehry (Les Inrocks)

On April 5, a large crowd assembled in the Parc des Ateliers for a groundbreaking ceremony to hear accolades from Maja Hoffmann, Frank Gehry and the mayor of Arles. It had been nearly six years since Maja and Frank had unveiled the original design in July, 2008.

The sentiments they expressed that day had a more melodic tone, rather than celebratory. Getting through the whole arduous experience produced an evocation of immense relief (soulagement), like marathon runners at the finish line, breathless.Les Inrocks magazine quoted a sardonic Frank Gehry, “The French are a complicated people. Maja knows how to get it done.”

2014: Sam Stourdzé Named New Director

In the community of French photography, you can pile the elite directors of festivals, museums and exhibitions into a minivan. Among those with a reserved seat was Sam Stourdzé, director of the Élysée Museum in Switzerland, an institution dedicated to photography.

His appointment as the new director of Rencontres d’Arles was announced in April, 2014, a week after the groundbreaking.

While Stourdzé lacks Hebel’s narcissism and quirky talent for publicity, he brought to Arles the impassioned, yet rigorous, management style of a museum director. In his first festival season, 2015, he reduced the number of exhibitions to 35 from 50.

In 2016, Stourdzé more than doubled the number of artists exhibiting, from 113 to 250, at 25 locations. Attendance remained glorious, topping more than 100,000 visitors.

Of tantamount importance is a harmonious relationship between Les Rencontres d’Arles and the Luma Foundation, which has assured Stourdzé and his team of the festival’s autonomy.

2015: Arles’ Clout in French Photography

In the winter of 2015-16, I caught myself saying that it’s not hard to see how the surging currents of French photography all flow through Arles.

The Jeu de Paume, Paris, had an exhibit of Philippe Halsman, co-curated by Sam Stourdzé. One stop on the Paris Métro put me at the Grand Palais for a retrospective of the Arlesian Lucien Clergue, co-curated by Christian Lacroix, a native of Arles, and François Hébel.

2016: Frank Gehry Structure Named

The building designed by Frank Gehry was designated the working title of “The Center for Human Dignity and Ecological Justice” to embrace the intertwining principles of human rights and the right to a healthy environment.

2017: Annie Leibovitz Exhibit

The Luma Foundation acquired the archives of the American photographer Annie Leibovitz – The Early Years, 1970-1983. The photographs were on display in the Grande Halle of the ateliers from May until 24 September. A mild irony: François Hébel hung some photos of Annie Leibovitz in 1986 when the ateliers were first used as exhibit space.

2017: Les Rencontres d’Arles

Les Rencontres d’Arles organized exhibits in the Parc des Ateliers in L’Atelier des Forges, and La Mécanique Générale. The numbers: 125,000 visitors (up 20% from ’16), 250 artists, and 40 expositions in 25 locations.

2018-19: Les Rencontres d’Arles

Rencontres d’Arles wrapped up its 2018 season by announcing a record attendance of 140,000 visitors, an increase of 12% from 2017. There were 36 exhibitions in the formal program, along with another 24 in associated programs.

2019 was a record shattering summer with 145,000 visitors at 51 exhibits to celebrate the festival’s 50th anniversary.

Paul Goldberger: The Frank Gehry Biography

Down through four decades from his perch at the New York Times and The New Yorker, the architecture critic Paul Goldberger covered Frank Gehry, who was…”arguably the most famous architect in the world…” he wrote. His intimacy with the man and his work made him a natural to pen a biography. With a pleasant flowing style that is an expression of his congenial personality, Goldberger chronicles, with entertaining details, the journey of Frank Gehry in “Building Art” (September, 2015). Goldberger reveals the gift France gave Frank Gehry: a glimpse of what architecture could be. Gehry spent a year in Paris in the early 1960’s working with architects. The Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, and the creations of Le Corbusier were an epiphany, confirming what he sought to feel about architecture. The American Center in Paris was Frank Gehry’s first project in France. Opened in 1994 with sweeping curvilinear surfaces and a jutting Cubist profile, the building was shuttered in 1996 due to financial mismanagement. It now houses a national museum of cinema. In 2004 came the opportunity for Frank Gehry to renew his attachment to France. Bernard Arnault, chairman of the French luxury conglomerate LVMH, approached him to design a museum for the Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. The Foundation Louis Vuitton was inaugurated in October, 2014, six months after construction began on Frank Gehry’s structure in Arles.

In his book, Goldberger’s noted Luma Arles in a compact 220-word summary.

Tributes: The team of curators and artists who are working with Maja Hoffmann to actualize Luma-Arles are: Tom Eccles, Bard College Director (New York), Hans Ulrich Obrich, co-Director of the Serpentine gallery (London), Beatrix Ruf, director of the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), and artists Philippe Parreno (Paris) and Liam Gillick (New York).

##