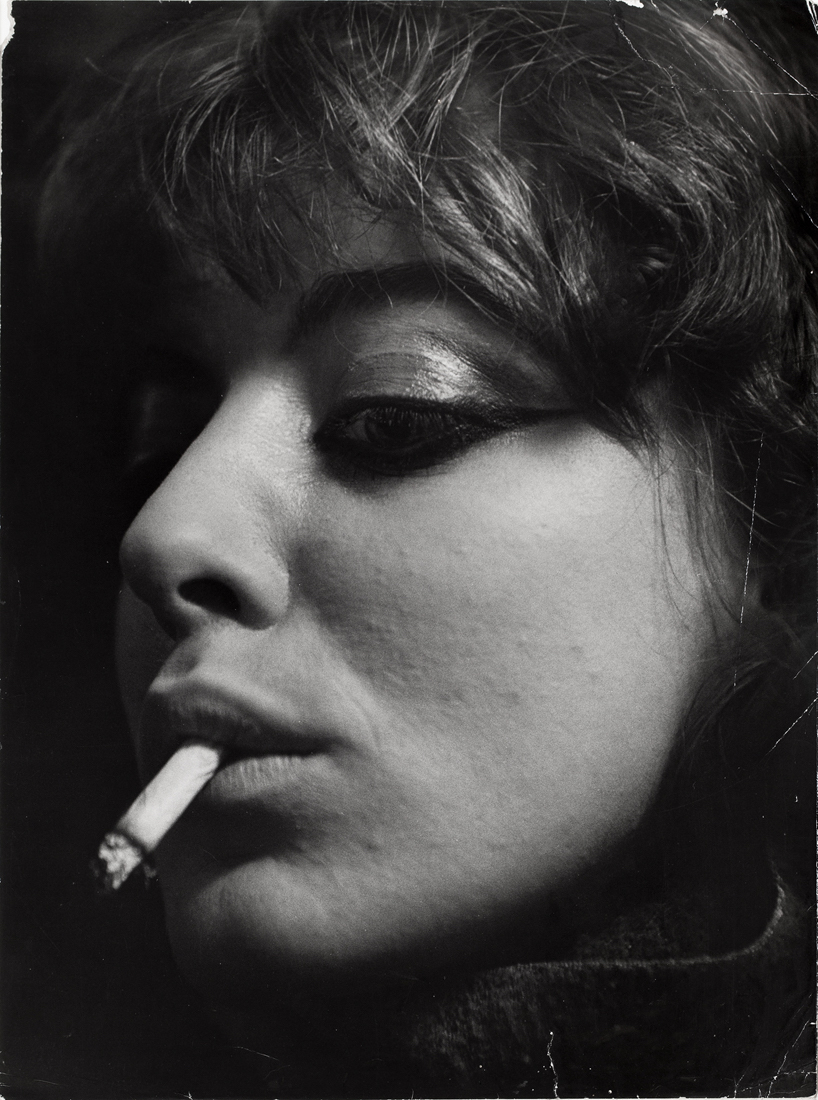

Vali Myers (Ann) before her mirror, Paris, 1953, Ed Van der Elsken, Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam. © Ed Van der Elsken / Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

“Photography, because it preserves the appearance of an event or a person, has always been closely associated with the idea of the historical. The ideal of photography, aesthetics apart, is to seize an “historic” moment.”

About Looking, John Berger

Among the galleries of indelible images of Ed van der Elsken at the Jeu de Paume, those of his Paris years stir one beyond speaking — none more so than the utterly intimate gaze of a dark visionary gamine, Vali Myers, around whom men purred and artistic women reveled.

From first sight of Vali, Ed van der Elsken was in her thrall. His camera fell in with her, and with her magnetic visage, at times angelic, at other moments ghost-like. The imperishable images of Vali are a touchstone of a huge raw talent.

Vali’s singular presence was the seed of a transforming experience in Paris that reverberates throughout Ed van der Elsken’s work in photography, shaping his craft, like water does stone.

Paris: A Rite of Passage

In 1950, the photographer Ed van der Elsken left Amsterdam for Paris, a more serious world for art. He took a job in the darkrooms of the Magnum agency, developing prints for Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. In a short time, he found that commercial photography held no charm. Something in him disdained celebrity.

The early 1950’s in Paris were his incandescent years when anything could be dared; his primal days of an existence completely riveted on the camera as an extension of his self, constantly recording experience.

His camera found its objects among the deracinated carefree youth who lived a marginal bohemian existence in the cafés and boîtes on the Left Bank. The gritty black and white images are haunting traces of lives interrupted, unhinged – une vie intérieure of emotional nihilism.

Among the troop of lost youth, van der Elsken’s lens returned again and again to the ravishing, sultry, and disheveled goddess of the dark streets, Vali Myers. She was his muse, his rite of passage from an image-maker to a savage street photographer, a sort of visual anthropologist.

While at Magnum, van der Elsken met the photographer Ata Kandó, a brilliant documentarian. They married in 1954, and moved to Amsterdam the following year.

In 1953, Edward Steichen, the head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, curated an exhibition “Postwar European Photography,” with 18 images of Ed van der Elsken. A precious moment arrived when Steichen suggested that the Paris images be fashioned into a photobook.

Love on the Left Bank – 1956

An immediate sensation, van der Elsken’s photobook “Love on the Left Bank” bracketed the photographs with a fictional narrative of Ann, a bohemian living in Paris. From the dust-jacket of the original 1956 English-language edition:

“A story in photographs about Paris – the Paris of the young men and girls who haunt the Left Bank. They dine on half a loaf, smoke hashish, sleep in parked cars or on benches under the plane trees, sometimes borrowing a hotel room from a luckier friend to shelter their love. Some of them write, or paint, or dance. Ed van der Elsken, a young Dutch photographer, stalked his prey for many months along the boulevards, in the cafés and under the shadow of prison walls. Whatever may happen in real life to Ann and her Mexican lover, their strange youth will be preserved ‘alive’ in this book for many years.”

The narrator is Manuel, a young Mexican on the loose, whose gauzy thoughts convey his unrequited love for Ann. George Plimpton opined that while the photographs are “amazing,” the text was “mawkish and unfortunate,”

The photographs of Vali Myers (Ann) – magnetic, mystical and mercurial – remind you that there is nothing brittle about living a visionary existence. Call it hidden depth. Whatever, without Vali the book would be soulless.

The groundbreaking book has been reprinted by Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Vali Myers (Ann), Roberto Inigez-Morelosy (Manuel) et Géraldine Krongold (Geri) Paris, 1950, Ed van der Elsken Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam. © Ed van der Elsken / Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

An Ode to Vali Myers: George Plimpton

In the spring of 1958, the Paris Review featured self-portraits by Vali Myers, accompanied by a vivid tribute by George Plimpton.

Plimpton came in Paris in 1952 to co-found the Paris Review with Peter Matthiessen and Harold L. Humes. Despite his patrician roots and lanky preppy good looks, Plimpton was a noceur – a lover of the night life and its marginal personnages.

At times during the early 50’s, Plimpton found himself in some left bank boîte or cafe – La Petite Source, La Chope Gauloise, Le Monaco, L’Escale, La Rose Rouge – in the presence of Vali, or in her hotel room.

In the Paris Review, Plimpton’s discerning ode evokes a fascination and a fondness, a testament to Vali’s seductive allure.

“Vali came to France just after the war. Still under twenty she became at once the symbol and plaything of the restless, confused, vice-enthralled, demi-monde that populated certain of the cafes and boites of the Left Bank.”

“Her dancing is remarkable—a sinuous shuffling, bent-kneed, her shoulders and hands moving at trembling speed to the drumbeats.She wears blue jeans, a man’s shirt pulled in at the waist by a wide black belt, and worn red ballet slippers that she often kicks off to dance in flat-splayed bare feet.”

“You saw in her the personalization of something torn and loose and deep-down primitive in all of us—and, Man, you could see it moving right around in front of you in ballet slippers and a man’s shirt.”

“Vali, in her early days in Paris, lived on practically nothing. Her few belongings were scattered throughout the Quarter in cafes, chambres de bonnes, in studios where she would sometimes sit for an artist. She carried her prize possessions with her in a wire carrying-case shaped like a bird-cage. In it she bad a bandana, her eye make-up and face powder, a volume of poetry by Thomas Chatterton, her art materials, and a curious piece of fur shaped like a miniature fox with two bead eyes embedded at one end: a keepsake she refers to as ‘the feeley and which she talks to from time to time, and often dusts, heavily, with face powder.”

Plimpton goes on to describe how Vali locked herself up in an apartment with her husband for years. Ever the gentleman, George omits the reason: a torrid addiction to opium.

Harangued by immigration officials, Vali and her husband would leave Paris in 1958 to live in a wild canyon outside of Positano, Italy. There she would replace her “feeley” with a real fox.

Ed van der Elsken: Avant-gardiste

On August 2, the New York Times published the obit of Gösta Peterson, a Swedish-born photographer, who broke color barriers with his magazine covers of a black model Naomi Sims.

The break through arrived on Aug. 27, 1967: Ms Sims appeared on the cover of a special fashion section of The New York Times Magazine, a first for a publication with a racially mixed readership.

Flashback. In 1953, Alexander Liberman, the legendary art director for Vogue, caught the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art on “Postwar European Photography,” which included 18 photographs of Ed van der Elsken.

Alexander Liberman championed photographers in the pages of Conde Nast – William Penn, Cecil Beaton, Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, and Annie Leibovitz, among others. Despite the talent he nurtured, Liberman proclaimed, “Photographers were not artists.”

What mild irony came calling when he approached a photographer about doing a fashion shoot for Vogue who disdained commercial aspects: Ed van der Elsken.

The acceptance by van der Elsken was conditional: he wanted to use women of color in the ads. The deal collapsed.

With the publication of “Love on the Left Bank,” van der Elsken sought out an American publisher. He received an adequate offer, yet the publisher demanded that the photograph of Vali Myers dancing with a black man be removed from the edition.

The response by van der Elsken was immediate: no censoring of race. There would be no American edition.

Ten years before the published photo of Naomi Sims by Gösta Peterson, Ed van der Elsken was an avant-gardiste, pushing out racial boundaries.

Patti Smith – Chelsea Hotel, 1971

In 1971 and in need of funds, Vali Myers ventured to New York City. She stayed at the Chelsea Hotel where she sought to sell her paintings.

There she met Patti Smith, who had fallen deeply in love with the playwright Sam Shepard. In Vanity Fair, Patti wrote about her memorable encounter with Vali:

“In the summer of 1967, at 20 years old, I boarded a bus in Philadelphia and headed to New York City. Only moments before, I had found a battered copy of Love on the Left Bank sitting on a sale table outside a used-book stall, across from the bus station. Attracted to anything French, I opened it and was greeted by a dark and intriguing café scene on the grittier side of the City of Light. It was Jack Kerouac, Parisian-style. I was especially captivated by the image of a girl, the likes of whom I had never seen before. She was Vali Myers, the Beatnik gypsy mystical witch who reigned over the rain-soaked streets. With her wild hair, kohl-rimmed eyes, loose raincoat, and cigarette, she offered herself with abandon and self-containment. She mirrored what I aspired to aesthetically—to be unconscious of style, yet style itself. Her subterranean world seemed emblematic of all I hoped to attain: in a word, freedom. These images, shot in the 50s by Ed van der Elsken, melded the documentary with art. I carried them within me as I ventured into new territory and a new life.

In 1971 the same Vali Myers, with a live fox on her shoulder, entered the lobby of the Chelsea Hotel, in New York, where I lived with Robert Mapplethorpe. She was then a tattooist, among other things. Recognizing the girl in the rain-pitted mirror, I gathered my courage and asked her to tattoo a lightning bolt on my knee, and she consented. And so she touched me first as an image and then as a human being, and I am happily branded for life. I still have my tattoo, and those images of an unobtainable but brutally familiar nightlife. They have always been with me, for they are, like Vali herself, unforgettable.”

Vali also fashioned a tattoo for Sam Shepard, a crescent moon between his thumb and forefinger, which Patti mentions in her plangent tribute to her recently deceased lifelong friend in The New Yorker,

Vali Myers (Ann), Paris, 1953, Ed van der Elsken. Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam. © Ed van der Elsken / Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Film: Death in Port Jackson Hotel, 1972

In 1972, Vali made a visit to Edam to reunite with Ed Van der Elsken. In turn, he visited Vali in Positano. The docufilm’s title is taken from the name of a drawing that Vali is working on in her kitchen. Shot in cinéma-verité, the film is unstructured.

The poignant moments are when Vali is talking about her street mates in Paris who committed suicide, as well as her opium addiction. She speaks about her slavish dedication to her drawings, which can take more than a year to complete. Attended to by a lover and a gaggle of animals, Vali’s hermetic secluded life puts no constraints on her feral artistic imagination.

The Years Have Their Closure

Ed van der Elsken’s career continued to flourish. He published another 14 books and produced about twenty films in collaboration with his third wife, photographer Anneke Hilhorst. From 1971, he lived with Anneke and their son, John. in Edam. He passed away, at age 65, in December, 1990.

Vali Myers lived in Positano with Italian artist Gianni Menichetti until 1993 when she returned to Melbourne. She opened a studio in the heart of the city. Before passing away at age 72 in 2003, she told a local newspaper: “I’ve had 72 absolutely flaming years.” Her prints are available from the Outré Gallery.

The bright, clean, white space of the Jeu de Paume

Jeu de Paume

“Museums do not so much arbitrate what photographs are good or bad as offer new conditions for looking at all photographs,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography.

Readily accessed from the rue de Rivoli, the Jeu de Paume is a bright, clean white space devoted to the image – photography, video and cinema.

Light floods onto its ground floor. From the windows, the city drifts into view – a ferris wheel, the majestic sweep of the Place de la Concorde, the impassive edifices of the rue de Rivoli, the Tour Eiffel, and the silent movements of strollers in the Tuileries Garden.

You feel within the city and, in the same instant, protected from it.

The Jeu de Paume embraces images with a modular design — in the basement floor, a video room, exhibition space on the second floor, along with a small cafe. A museum shop on the first floor may be accessed sans admission.

The Jeu de Paume was built in 1861 during the reign of Napoleon III to house tennis courts. Paume means palm, as the Jeu (the game) was originally played by hand, before the use of racquets. Dating to the middle ages, the game was the domain of French royalty.

Trivia: Peter Matthiessen stated that his intent in co-founding the Paris Review was to provide a cover for his CIA activities, which consisted of keeping tabs on Americans in Paris. In the oral history George, Being George (Plimpton), Matthiessen revealed the spot in Paris where he would meet with his CIA supervisors: the Jeu de Paume.

Ed van der Elsken, La Vie Folle

The exhibition, which runs until September 24, presents a large selection of some of his most iconic images: shots of Paris from the 1950s, figures photographed on his numerous travels or in his native Amsterdam from the 1960s onwards, as well as his books, and excerpts from his films and slide shows, particularly Eye Love You and Tokyo Symphony.

Jeu de Paume, 1, place de la Concorde, 75008 Paris, métro Concorde, website

Hours: Tuesday: 11am – 9pm, Wednesday – Sunday: 11am – 7pm

Closed Monday (including public holidays).

The exhibition is produced with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in collaboration with Anneke Hilhorst and Han Hogeland, University of Leiden, the Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, and the Jeu de Paume, Paris.