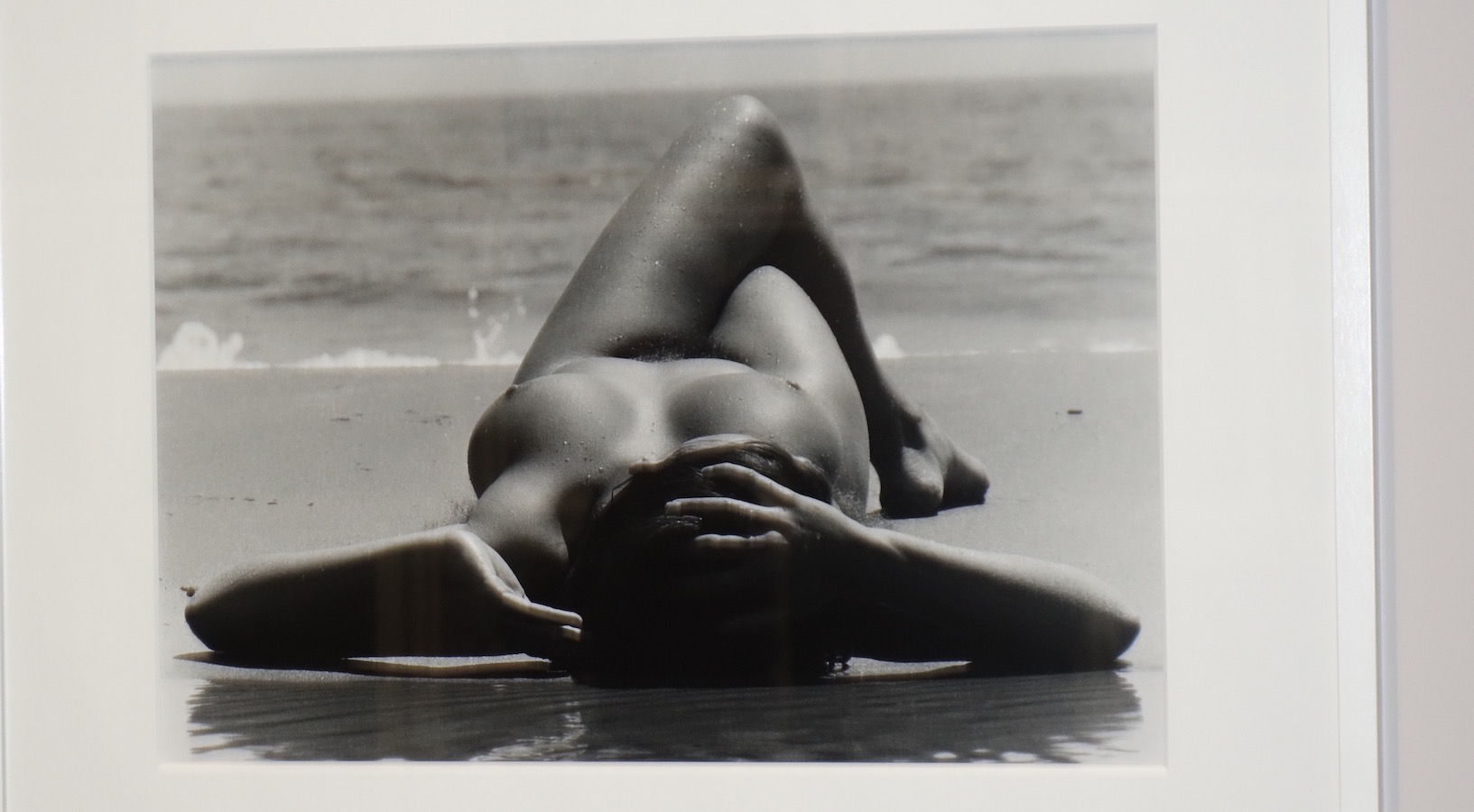

Nude by Lucien Clergue at Le Grand Palais

Passages: His iconic presence in Arlesian culture defies simple grief. Jean-Maurice Rouquette, co-founder of Rencontres d’Arles, died on Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2019.

Lucien Clergue (1934 – 2014) was the first photographer to be elected to the Paris-based l’académie des Beaux-Arts. In 2013, he took on a year-long term as the President of the académie.

Lucien accepted the post so that he could “defend photography.” Amplifying a perceived neglect of his craft, he said, “Photographs are the poor relatives of everyone.”

Brimming with energy and charm, imagination and talent, Lucien soared to great heights in photography, a fate he was to believe in with all his being. He also bequeathed to his native Arles – his lifelong home – an unalterable destiny as a fervid celebration of photography each summer.

Perched on the Rhone in Southern France, Arles wears a patina of antiquity on every public surface – cramped lurid biscuit-colored edifices and decaying gray stones, all of which dismantles modern memory into sepia tones.

Among Lucien’s oeuvre are photographs of female nudes posing in the savage terrain of Camargue: stunning meditations on beauty and nature, on the surfaces of life and art, brilliantly sculpted by shadows and dimming light, crafted by unending days at the water’s edge.

The narrative which follows is like looking out the window of a train passing through imperishable times populated with enthralling personalities. It is an elementary selection, a glimpse of a life lived large.

The passages are drawn from video interviews shown at an exhibit of Lucien’s images at Le Grand Palais in Paris in the winter of 2015-16. The videos were produced by François Hébel, who was, for more than a decade, the director of the photography festival in Arles, and Christian Lacroix, the fashion designer, patron of the arts, and native Arlesian.

François and Christian reach far back with Lucien; the strength of their friendship is woven, tenderly, into the dialogues.

Abbreviations: LC: Lucien Clergue. JMR: Jean-Maurice Rouquette, childhood friend of Lucien and curator of art for museums in Arles. WC: Wally Bourdet, native Arlesian who posed for the nudes of Lucien Clergue.

Un Enfant de Guerre

JMR: What should be noted is that we were teenagers during the war, and nothing can be understood without going back to that tissue of war, of deprivation and of hostility.

LC: My birth led to my mother being handicapped as doctors told her that she should not have children. I lived alone with my mother. To escape the bombardments, the Mayor of Arles sent kids to a camp. When I returned in Dec ’44, my mother met me at the train station, and announced that we no longer had a house (reduced to rubble).

LC: I only knew my mother as sick. She suffered terribly. I even had to wash her body. She died when I was 18. What was remarkable about my mother was that she wanted me to be an artist. She made me take violin lessons.

JMR: When his mother passed away, there was no money to pay for his violin lessons. It was then that he met a baker who taught Lucien how to develop photographs in the gazebo of his shop.

JMR: From his first encounter with the camera, Lucien understood the difference between taking snapshots or portraits, and creating a series of images. He grasped that photographic talent embodies a vision through a sequence of images that derive their meaning from being connected to one another. His first series were variances on images of death.

Influences

LC: With my violin, I devoted two to three years to six sonatas of Bach. It was with these sonatas that I learned everything because of Bach’s structure and composition.

LC: At Easter ’53, at the time of the Féria, I was in the audience when a bullfighter dedicated his performance to a personnage. I asked someone next to me who it was. The response: Picasso. I left the arena and went to my place to fetch my photographs. I was hardly 19, and had only been shooting for a year. I waited at the exit for Picasso. When he came out, I put my photographs under his nose. He said, “I would like to see others.”

LC: In the same year, I bought a magazine called Photomonde. I was overwhelmed by the photo on the cover: a famous nude by Edward Weston. There were photos by other masters within its covers. In an instant, the world of photography was revealed to me.

LC: On November 4, 1955, two years after meeting Picasso, I went to his house in Cannes where he viewed my photographs.

LC: Bach, Picasso, and Weston. Voila, my trio.

Note: Lucien had a twenty-year association with Picasso, who introduced him to Jean Cocteau. In ’57, Lucien’s photos of Denise, who modeled nude on the beach, appeared in Corps mémorable, with a cover by Picasso, and poems by Paul Eluard and Cocteau).

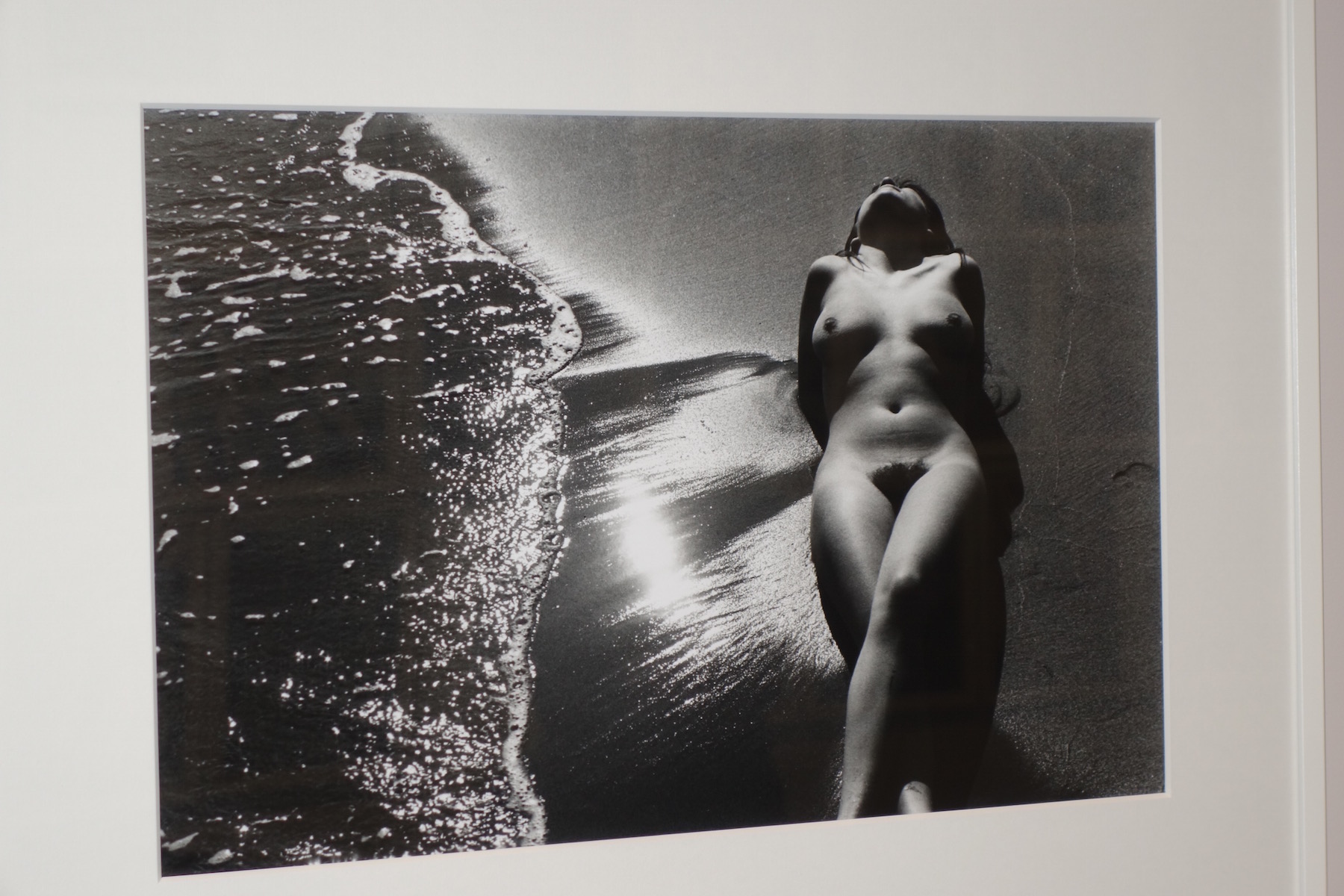

Nudes by Lucien Clergue at Le Grand Palais

Nudes

LC: Probably, the first nudes that I made in ’56 were a reaction to the suffering of my mother, a desire to photograph young women full of life, wildly health. I needed voluptuous woman with generous curves.

WB: The photographs of nudes corresponded to a counter-image of the anguish in his life growing up with a sick and fragile mother.

LC: I was alone in my apartment developing photos of carrion, cemeteries and ruins. Little by little, friends disappeared as it was no fun being around these morbid images. I was afraid of being alone. I said to myself that I have to take photos of girls. It was then that a girlfriend posed for me on the beach in Camargue.

WB: Lucien took photos of nudes without their heads because he wanted images that were timeless, and he felt that heads dated the images. Then, we were often in such uncomfortable positions, that it was dreadful. A third reason is that he could put himself in the place of your head, endowing himself with a vision that you had of yourself.

LC: Censorship was fierce in the 1950’s. My editor was obsessed with being taken to court to create some publicity. There was a tribunal in Bordeaux that ruled where there was the image of a head, there could be no pubic hair, and, likewise, where there was pubic hair, there could be no head. I was saved.

WB: We left at 6:00 a.m. for the Faraman Lighthouse in the Camargue, and returned at 8:00 p.m. Lucien would shoot in the morning before the sun was high in the horizon. During the day, he would prepare for how he was going to shoot later in a dimming light.

LC: When I talk about the proportions of the body, it is something that people do not understand. In my youth, I went to the museum in Arles where I viewed a copy of the statue of Venus, and dancers. I would take my handkerchief and measure the distance between the breasts, between the breasts and the belly button, and between the breasts and the sex. I studied these proportions to arrive at a ‘golden ratio.’

WB: There was a meaning for me to be naked in the sand, water, salt and dead wood. There was a communion between me and nature. I shared that with Lucien: an escape from the hard life in Arles to where you immerse yourself in wildness of nature.

LC: Christine was a model that made a wonderful impression on me for her kindness, beauty and proportions of her body. She possessed the ‘golden ratio,’ an absolute beauty. She posed in the summers of ’62 and ‘66 and was on the cover of Née de la Vague.

WB: Lucien and I had the same things to say, but not with the same means. I posed not because I wanted to appear pretty. I wanted to participate in something that was of interest to me. Lucien said that I was “made of granite.”

Nude by Lucien Clergue at Le Grand Palais

Musée Réattu: Photography Cometh

JMR: Around ’57, I moved into Arles’ Musee Réattu that was totally in ruins. No collection. No money to purchase anything. Lucien began to pester me: there was no photography museum in France; you have to show photography as great art.

LC: In 1961, I went to New York. I dashed to MOMA to see Guernica by Picasso. There, to my great surprise, you had to go through rooms displaying black and white photographs to reach Guernica. I said to Jean-Maurice that to view the world’s greatest contemporary painting, you have to walk through photography. That moment in New York was capital in making us move forward.

JMR: We sent out letters to photographers asking them to donate prints for the museum. Two photographers refused to donate: Cartier-Bresson and Avedon. We found patrons who purchased their images for the museum. After a month, we had enough prints to display in a room. We opened in ’65.

LC: In ’65, I was introduced to the American Jerome Hill who lived in Cassis. He said that he had prints of Edward Weston. I told him about my admiration for Weston and about what we were doing in Arles. He offered me ten prints for the museum. At that time, the Mayor of Arles gave his consent for the second floor of the Musée Réattu to be dedicated to photography.

Les Rencontres d’Arles: Int’l Photography Festival

JMR: The revolutionary fervor in the spring of ’68 incited citizens in Arles to demand changes in the Festival of Arles. We said that the only thing we have that is free is photography. We proposed bringing three photographers to present slides of their work in the reception room at City Hall. There were lines out the door until 3:00 a.m. The next year we set up about 400 chairs in the courtyard of the Musee Réattu. And it took off like that.

LC: When we had our first exhibition at Les Rencontres, I called Jerome Hill and asked for other prints of Weston. He sent them to us. When Jerome passed away, those photos remained in Arles.

JMR: We invited the renowned writer Michel Tournier to join us because we needed a hero. Lucien was a born showman who adored a performance. There had to be someone glorious to present things.

LC: As soon as we started Les Rencontres, I began to network with photographers. In 1971, I made a world tour. In Carmel (CA), I met Ansel Adams in Carmel and invited him to attend. Back in Arles, with the little money that we had, we invited Adams. If it did not work out, we would at least go out in style. He came in 1974, and taught a workshop. When he returned home, he gave a press conference at which he wondered how the young people of Arles could do such amazing things for photography when we are not able to.

Les Rencontres d’Arles runs from July 2 – Sept 23, 2018, opening week July 2-8, 2018. The festival attracts more than 125,000 photography enthusiasts.

Postscript: For the Love of Jazz

Summer 2011. A pure azure sky, light streaming across an expansive graveled terrace, views of the vast green vines of Châteauneuf-du-Pape extending to the horizon. Accompanied with gleaming glasses of luscious wine, guests of the Château de Nerthe drift among works of art.

On display were photographs by Lucien Clergue. He appeared on the terrace, approachable, and open to talking about his work and that of others.

Lucien Clergue (deep blue shirt) at the Château de Nerthe, July 2011.

What I discovered was a missing thread, one that had not been woven into the narrative of his life at the retrospective at the Grand Palais. Lucien’s fervent love of jazz, a topic that consumed our conversation, of musicians listened to, when and where. He was off the next month to take in Wynton Marsalis, among others, at “Jazz in Marciac,” France’s premier jazz fest.

He had become what he always dreamed and worked for, an artist, his name inextricably linked to photography. Among his many virtues count modesty and generosity, as well as a great natural talent and acquired perfection.

Les Clergues d’Arles, an exhibit of his photographs, ran at the Musee Réattu from July 5, 2014 to January 4, 2015. There had been cancer. Lucien Clergue passed away on Nov 14, 2014.

Information on the photographs of Lucien Clergue: Anne Clergue Gallery

##